Part 1. Invention | What is your motive?

Course Home | Part 1. Invention

Your Motive

Which of these motives is yours, right now?

- Reassure: stop your audience worrying about something. When a company is struggling, or a nation comes under attack, leaders reassure.

- Unsettle: shake your audience out of their complacency. When activists wonder why people aren’t worried about (say) climate change, they seek to unsettle.

On any given occasion, every speaker has (broadly speaking) one of those motives at heart.

If you’re (say) a property developer at a local government planning appeal, you might attempt to reassure; or if you’re a local resident opposed to the development in question, you seek to unsettle.

Unsettling is key to so many speeches because audiences often think they know it all already; or profoundly resist hearing about something that’s uncomfortable. By unsettling first, you get their attention. From that point on, you may choose to provide reassurance – or not.

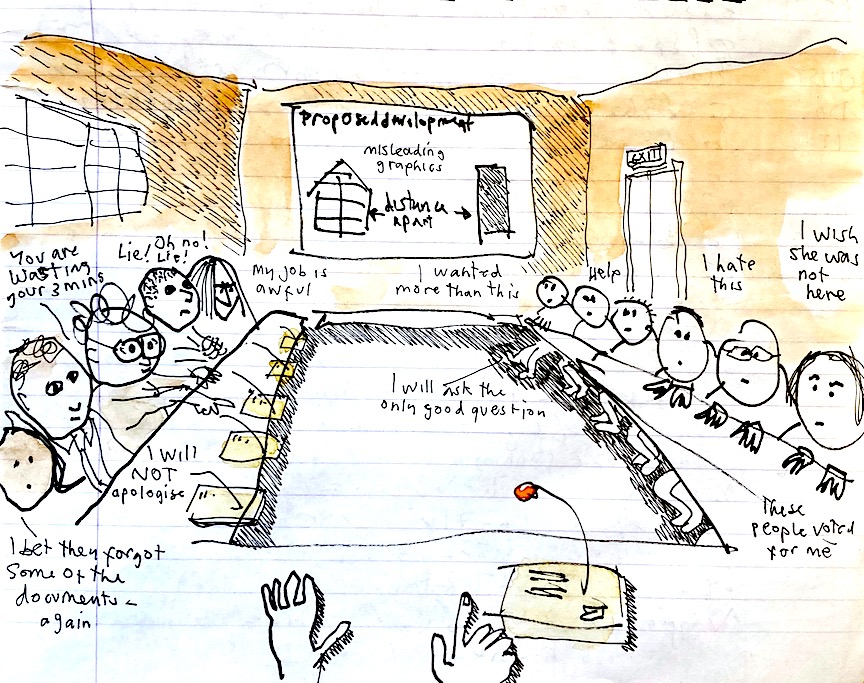

For what it’s worth, the picture above is my recollection of speaking at one of those planning appeals (as a resident). It was drawn a couple of days afterwards.

I had just sat down, and nobody told me to start talking – and the irritable chair told me I was wasting my three minutes. I talked fast!

***

There’s another way to think about this: typically, a speech is designed to inform, entertain, persuade or inspire. It might do more than one of those, but the central purpose is just one of them. Here are a few examples, to show what I mean.

- A teacher might like to be inspiring, but needs most of all to inform.

- A politician might like to entertain, but persuasion comes first.

- If you’re delivering a speech at a wedding, you may want to entertain and inspire, but you won’t need to do much persuading unless the wedding is somehow controversial (“Hey, believe me, the groom really isn’t such a bad chap…”).

- At a funeral, you may wish to inform people about the person you have lost, but you probably want most of all to inspire listeners – to appropriate feelings of sorrow and love.

***

Spectrum Of Communication

It must surely be obvious that to find – and achieve – your purpose you need a reasonable sense of your audience. In my own experience, you can never know enough about the specific people you are talking to. Sometimes, unfortunately, you know very little.

For instance: right now, you are my audience. You may be a stranger, you may be somebody I know already, you may be a member of my family. How am I to get the tone right?

So: find out as much as you can about your audience beforehand, and even as you speak.

As a result, you will tend to move towards the right on this downloadable spectrum of communication:

***