Rightly or wrongly, most of us talk sometimes about other people in their absence. This often deserves to be described as gossip. Most of us disapprove of it in principle, but still do it a lot.

And not only in their absence. Sometimes we talk about people in their presence.

About a year ago, somebody sent me a YouTube film showing a British comedian being interviewed on a north American TV show. He was sitting at a table, like on news broadcasts, rather than the usual chat-show sofas-and-armchairs, talking about his work with three people I didn’t recognise, at least two of them hosts of the show.

Over several minutes, the comedian talked in his very idiosyncratic way about his latest work and his hosts / the other guests found him to be amusing. But having started to laugh with him, they moved on to laughing at him. And at one point one of them referred to him as “he”.

I’ve forgotten virtually everything else about the interview except this moment. “It doesn’t feel good when you talk about me in the third person,” the comedian said. “It feels as if I wasn’t here.”

This was a very powerful moment for me, because it distilled an awkward feeling I’d had for a long time. As a journalist, I would meet people, get on with them variously OK or even very well, then go off and write them up, in the third person, for other people’s entertainment. As if they weren’t there.

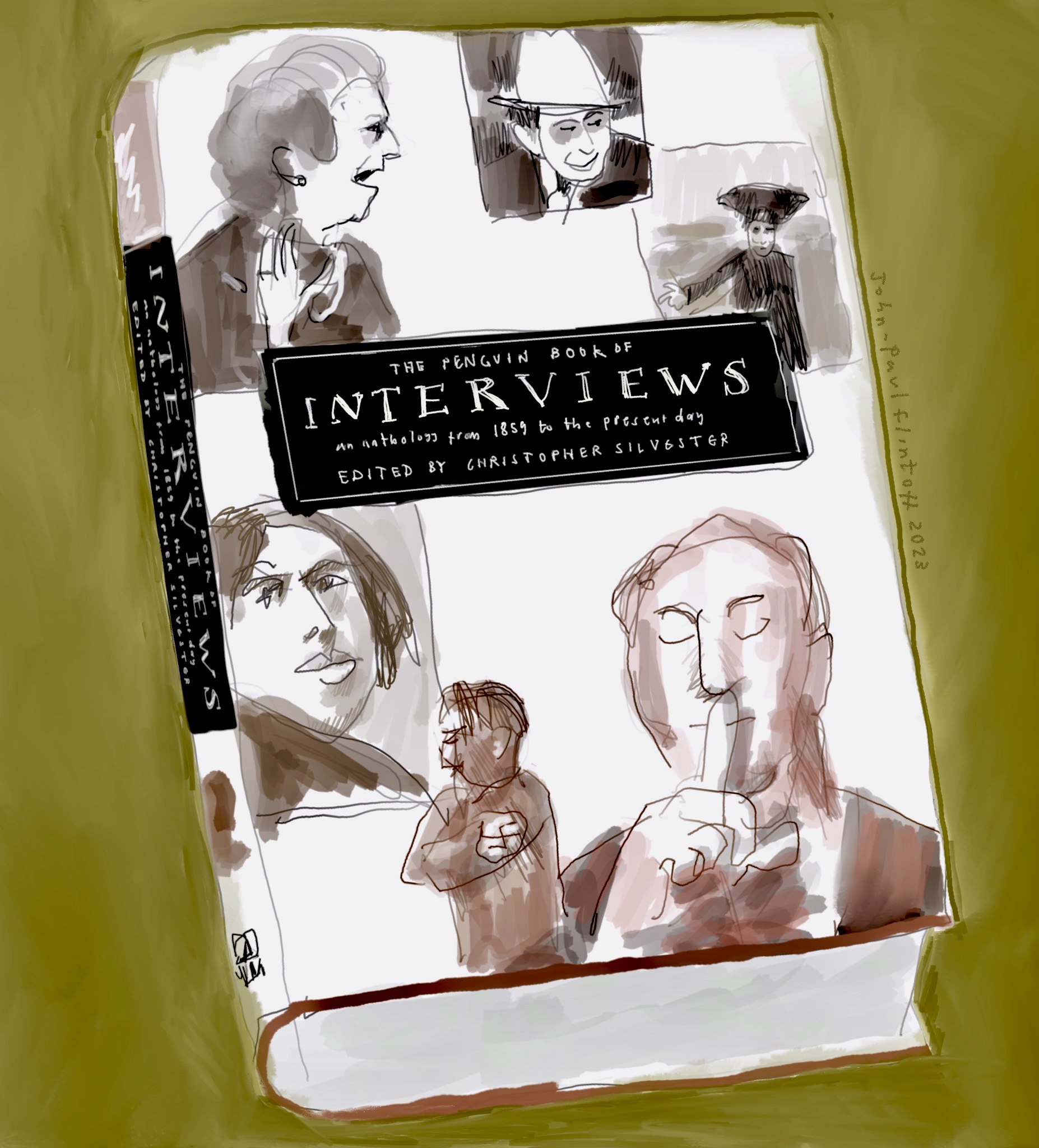

These thoughts have been stirred up by re-reading The Penguin Book of Interviews, edited by Christopher Silvester – a book that I bought and read avidly as a young journalist, when my aspiration was to emulate the bold, entertaining writers anthologised within it. I had little interest, then, in the bleatings of the people interviewed, who often said they disliked the experience.

Yes, I know how ironic that is. I was embarking on a career based on talking to people, and I wasn’t really interested in their bleatings.

I know better now. In the years since, I have wrestled with many of the problems outlined by Silvester in his introduction. And I’ve learned how painful it is to be told by somebody I interviewed that he felt “betrayed” by what I wrote.

His reaction, like the pained intervention of that British comedian on American TV, taught me that you can never know how people will feel about what you write, or say, about them.