Best Man Speech, Part 2: Arrangement

Welcome back.

This is the second of five steps towards making your Best Man speech a success.

In the previous episode, as they say on TV… You worked out some answers to why specifically you are giving your speech.

In this second part, which classical rhetoric calls Arrangement, you’ll decide on specific content, and structure.

Further down this page, I’m going to ask you to summarise the talk in just one sentence. The simplicity of the desired output (just one sentence) does not reflect the difficulty of achieving it (really jolly difficult).

And I have two more challenges, helping you to choose and shape the stuff you mean to include (facts, stories, etc). Please don’t feel overwhelmed. Take your time. And if you have any questions, let me know.

***

Interplanetary weirdness

There are many ways to assess what to include, and filters through which to understand what kind of effect those things might have.

I’m conscious that in what follows I might seem to suggest you should speak like some kind of interplanetary weirdo – utterly analytical, instrumental and inhuman. Far from it! You must definitely be yourself, when the time comes. And you should be a human (if you are one).

Arrangement is just a stage in the larger process – a stage in which you examine all your stuff, your material, afresh. Speaking for myself, I regularly stare at my stuff like an interplanetary weirdo, because it helps me find new opportunities to make it work better.

***

Past, Present, Future

If you speak in the past tense, you will almost inevitably deliver praise / blame, even if it’s only implicit.

The present tense is where you talk about the values that you share with your audience – things you do believe in, and things you strongly oppose. In that sense, it’s an opportunity to knit together a sense of unity.

The future tense is about the choices you / they can make, variously dreadful or thrilling.

As a broad generalisation, talks tend to start in the past and move towards the future; because as you have already established, you are looking to have a particular effect on that particular audience, and that effect can only take place in the future.

The easiest way to understand this is probably to look at actual speeches, and see how they handled it. More on that below.

***

Ethos, Logos, Pathos

Classical rhetoric has given us another important filter through which to consider our material. This involves looking for the right balance of the following ingredients – a balance that varies from one occasion to another.

Credibility. Who is the speaker, in this particular context? Rhetoric calls this Ethos. In practice, this varies enormously.

It is frequently assumed (by people lacking experience) that the speaker needs to be a big expert, incapable of error.

That’s sometimes true (“I speak to you today as the only person who has ever performed this kind of surgery”), but often the opposite applies, and the speaker addresses the audience as peers (“I’m just like you”).

Looking like a big-shot can be alienating. There’s a line that demonstrates this beautifully in the film Notting Hill. (It’s not “public speaking”, because it’s a conversation between two individuals, but I don’t believe that matters.)

It comes when the Hollywood movie star (Julia Roberts) tells the bookshop owner (Hugh Grant) that she’s an ordinary human, with a heart, just like him:

The line has been copied and parodied by many speakers, trying to reach an audience that’s assumed to be indifferent. (“I’m just a humble salesman, trying to make a living.” “I may work in Westminster, but I’m a native Geordie / Scouser like you.” And so on.)

Come to think of it, there are even times when speakers might usefully present themselves as a confirmed ignoramus (“I’m here today to tell you that I don’t have a clue what you are doing. Please help me,” or, “Mr Speaker, I don’t understand why the Prime Minister wants us to invade”).

Reasoning, or Logos. This is about the way in which a speaker builds a case around facts and interpretation of the facts, in order to make that interpretation appear to be the only possible interpretation – or the best available, anyway.

A common mistake, here, is to avoid any alternative interpretations. With experience, speakers learn to address those alternatives head on, and show why they’re mistaken.

Emotion, or Pathos. This can be any kind of emotional expression. “I’m so happy!” “I’ve never felt so lonely.” It needn’t be stated explicitly, with words, if the emotion is obvious – as you saw in that clip from Notting Hill.

***

Challenge 3 | Make Your Own Mind Map

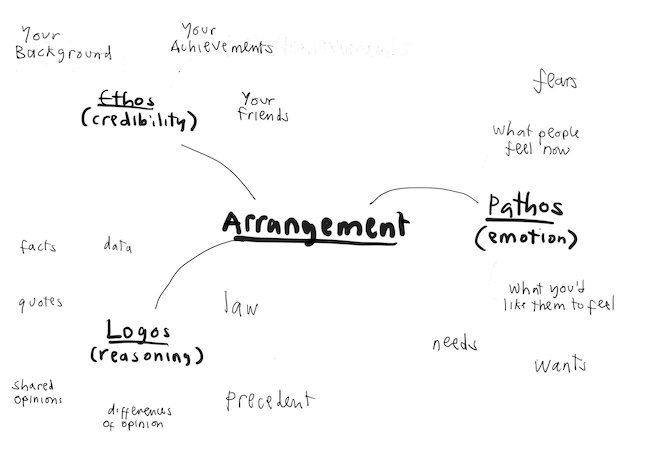

This mind map covers some of the things you might want to consider when auditing your own Ethos, Logos and Pathos.

Download a copy of that mind map, using the link below, and replace the generalised content with details relating to a specific talk you are going to / might make.

Modest Adequate Arrangement Mind Map.pdf (158.3 kB)

***

Challenge 4 | Write an outline

This challenge invites you to summarise your speech or talk in just one sentence, then one paragraph, then a bit longer.

If you do that here, in this Google Form, I’ll be able to read it.

You can start (and revise) the challenge here:

***

Challenge 5 | Improve the outline

This challenge prompts you to finesse the outlines you wrote, with particular focus on:

- Storytelling (as a way to make “information” more compelling

- Your “rhetorical enemy” (the thing you must argue against)

- Why you care about this (a better credential than any exam certificate or job title)

- Emotional variety (happy to sad creates one outcome, sad to happy another).

I made a video to help with this challenge. I’m putting it here, but it’s also embedded within the Google Form below:

If you type into the Google Form (as in previous challenges), I’ll be able to see your response. You can start (or revise) this challenge here:

***

Next time

In Part 3, we’ll be thinking about Style. Till then!