Emily B. is doing a brilliant job securing publicity for my book. She got me a commission to write 800 words for the Guardian.

This post is part of a series, introducing my book Psalms for the City.

Back to Main Psalms Page

It’s for a slot called “A Moment That Changed Me”. Here (below) is the copy I filed. Naturally, the piece as it eventually appears – if it eventually appears! – may be quite different. But I thought you might like to see the words just as I sent them.

I’ve formatted it exactly as I was taught to prepare my copy before filing, with my name spelled out at the top to avoid sub-editors making mistakes, a line break between each par, “STARTS” at the top and “ENDS” at the bottom.

There’s one big difference: I’m adding here the actual, original drawings that I mention in the story.

(The Guardian won’t have those.)

***

STARTS

By John-Paul Flintoff

This happened at school. It was the end of the day. Teachers sat around the hall, behind tables, waiting to help us chose our A Levels.At the table marked “Art” sat a teacher with a beard and a checked shirt. I didn’t know him, he’d never taught me. I sat down and told him I wanted to be an artist.

He was downbeat. Said something about it being “hard to be an artist” – may have used those exact words, or something similar. I’m not sure. It’s a long time ago. But whatever the words he used, I remember the feeling: it felt as if he said: “You, Flintoff, cannot be an artist.”

Would another teacher have said something different? Maybe. One, Mr Elliott, had told the whole class he read about me in the local newspaper (“Schoolboy Artist Brushes Success”) after I won a special prize, aged 14, in a painting competition for adults.

I’ve still got that newspaper cutting. I remember sitting on the wall outside the front of our neighbours’ terraced house, talking to the woman reporter. I was shy, found words difficult, but she wrote what I said in her spiral-bound notebook. This was the quote she used: ‘“At the moment I paint just because I enjoy it,” said John-Paul. “I’d like to be able to earn my living this way later on.”’

To see my photo in the paper, and that quote, was to believe I could do it. But the bearded teacher with the checked shirt seemed determined to destroy my dream.

Looking back, years later, I see that this is nonsense. I simply misunderstood him. But for whatever reason I went into writing instead: studied Eng. Lit. became a journalist – like that woman who interviewed me on the neighbours’ wall – and published books.

But a series of traumatic events, followed by a loss of work, then lost confidence in myself resulted in a breakdown at the end of 2017. I admitted myself to psychiatric hospital, with depression and anxiety. For a short time I was put on what nobody officially calls suicide watch. I was convinced there was nothing in life to look forward to.

One of the nurses told me I needed to “practice self-care”.

To me, the words conjured a picture of candles around a bath. I couldn’t see how this helped.

“Make friends with yourself,” he said.

Again, I was baffled. I understood the individual words, but not the sentence as a whole. I asked for clarification in a group therapy session.

The therapist said: “Imagine yourself, aged about four or five. Imagine that little boy coming into the room now… What would you say to him?”

I was stumped. Words failed me – me, the writer. I went back to my room, where I had a sketchbook and pens, and started drawing.

I drew a picture of myself as I am now, sitting opposite an empty chair. Then I drew the same scene, with a little boy walking towards the empty chair. Then I drew it again with the boy climbing onto the chair. He had a friendly smile, and I gave him a little speech: “Hello.”

Not knowing how to reply, the adult version of me just sat there.

Over the following weeks, I drew hundreds of drawings. Quite an artistic revival.

Many featured Little JP, with me – Big JP – holding his hand as we had various mild adventures.

Was this self-care?

Then one day, in another group session, I used words to describe myself that I would never use to describe someone else: “worthless c___”.

I looked around at the other faces: consternation. Plainly, they didn’t see me that way. But how could I stop thinking it? And then I remembered Little JP.

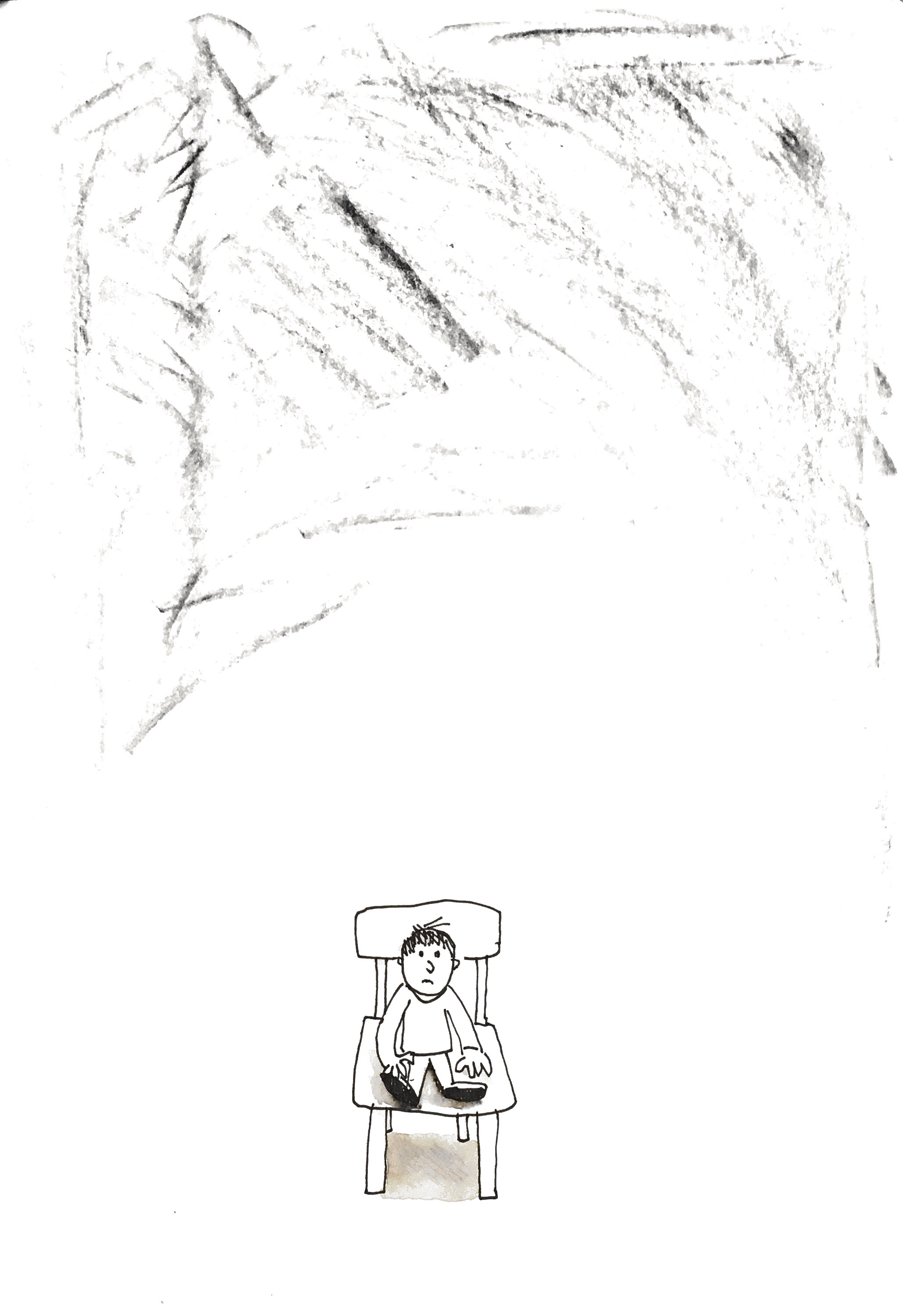

Back in my room, I drew a picture of the round-faced four-year-old me, sitting on a chair down at the bottom of the page, with a frightened expression.

In big letters, I wrote at the top: “Worthless C___”

And suddenly, finally, I could see what a terrible thing it was to speak – or think – of myself that way. How cruel, how brutal it was. And I stopped doing it.

Since then, my art has continued to flourish, alongside my writing. In lockdown, I sketched people’s portraits online to raise money for charity – one subject was Olivia Colman. And I used an online tool to draw collaboratively with people far away.

Best of all, I wrote a book – about finding peace in the places we call home – and I illustrated it too: 50 full-colour drawings, plus the cover – showing the view from my hospital window. Can you imagine how good that feels? I wanted to make art for a living. Forty years passed. And now I do.

Psalms For The City is published by SPCK.

ENDS

Some of this may have been familiar from previous emails. I don’t apologise for that.

On the contrary, I thank you for being one of the readers for whom I was able to work out ideas before submitting them to the Guardian.

You can watch me draw Olivia Colman here.