I told them to be brave / 3

[continued…]

"Life went on, but all the colours faded, and our home was strangely sad and empty. One of the things I miss most about my dad was being held by him."

Anne threw herself into peace work while trying to be a good mother and create a normal home.

“It was more than I was able to do. I was present, but always partly on another wavelength.”

Less than two years after Norman died, Anne married again

Her new husband was a long-standing friend, and the children were devoted to him, but they continued to suffer inwardly.

Then Ben was diagnosed with cancer and was told his leg would have to be amputated.

The illness went on and on.

“I got in touch with my grief just enough to be angry with Norman for not being with us for this long battle.”

She realised she had remarried prematurely, and separated, then divorced.

Ben grew weaker, and after several years he died. He was 16.

This second loss was devastating. “I wanted to die too,” Anne says.

Life felt devoid of meaning

But she still wouldn’t weep around the others.

“Every time I took a shower, I cried. Looking back, I realise that I was crying for Norman too.”

“I never saw my mother cry,” says Christina. “And I followed her example.”

Anne married for the third time, in 1974, to Bob Welsh – another Quaker, who had faced the prospect of prison for quitting the military reserves.

They recently celebrated 36 years together. “He’s been very generous, understanding and supportive. He didn’t know Norman, but he respected him very much. I’m extremely grateful for his greatness of spirit.”

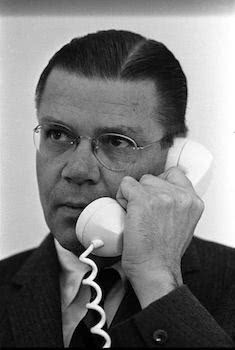

Norman had set fire to himself 40 feet from the Pentagon office window of the wartime secretary of defence, Robert McNamara:

Thirty years later, McNamara published a memoir acknowledging misgivings about the war, stirred up by Norman’s act, that he was unable to speak of at the time.

“I reacted to the horror of his action by bottling up my emotions, and avoided talking about them with anyone – even my family. I knew [they] shared many of Morrison’s feelings about the war.”

Others might have felt this served him right.

Anne wrote to McNamara, thanking him for his candour and telling him what kind of person Norman was. McNamara phoned to thank her for the letter.

“We had a surprisingly relaxed and candid conversation, as if we knew each other,” she says. “Norman’s death is a wound that we both carried.”

Norman’s sacrifice was well known in Vietnam.

Anne had received letters of support and thanks for years. She knew the North Vietnamese government had issued a stamp with Norman’s face on it, and named a street in Hanoi after “Mo Ri Xon”.

She had received condolences from President Ho Chi Minh, and an invitation to visit.

But she didn’t take up the invitation until the late 90s, after a Vietnamese man approached her at a talk and told her that when he was little, like other Vietnamese children, he had learned by heart a poem dedicated to Norman by North Vietnam’s poet laureate.

Anne flew to Vietnam in 1999, taking Christina and Emily with her – by now well into their 30s.