Take Your Work With You Everywhere | WTCTW 4

Carrying Work In Progress in my back pocket

Previously | Handwritten | Reputation | Word-Face | Next

When I’m working on a new book, I like to print it off and carry it around with me, to experience as a book as early as possible.

Hi, this is the fourth in a shortish series about Writing To Change The World (WTCTW).

I’m working on my next book at the same time as I write this series. It happens to be a book of poems, written and illustrated by me. It may or may not change the world – that’s not for me to decide. But I thought it might be helpful to share something about my work in progress, in hope it might give you some ideas. Take what you like and leave the rest.

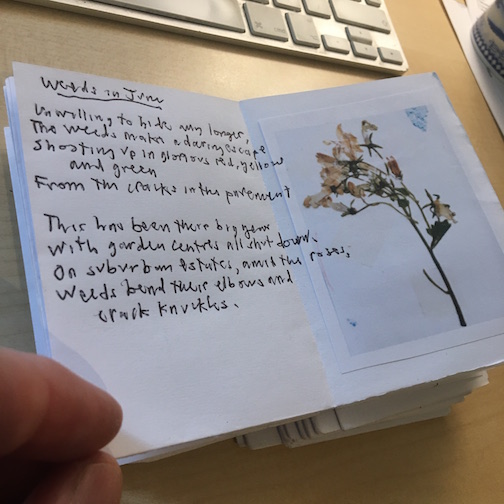

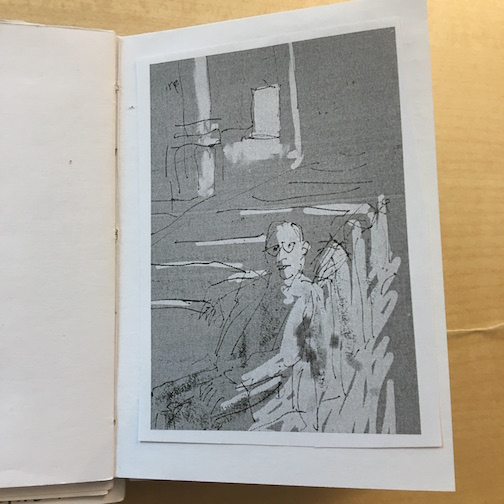

The picture above shows a double page spread, with an image on the right (where they tend to have most impact) and words on the left.

I’d previously written the words in an exercise book that’s on the desk beside me, and I’d created images quite separately. They’re all over the place: saved in the Procreate (art) app on my iPad, saved to Photos in my cloud account, and in the online storage of the printer I use in East London.

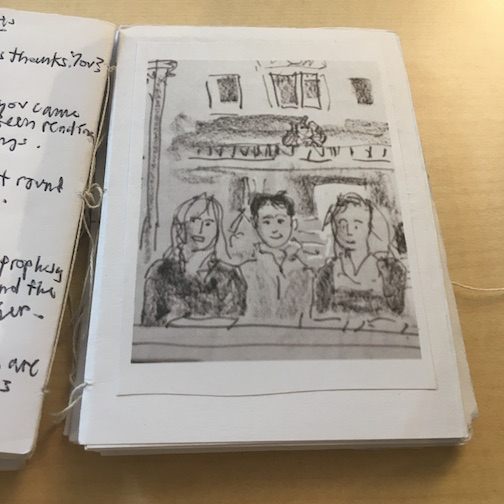

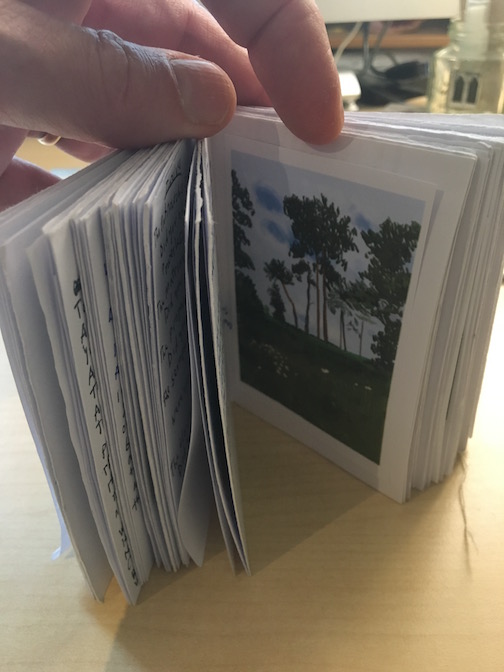

The point of the hand-stitched pocket-sized gathering-together you see in these photos is for me to get a sense of which pictures I’ve created might work best with which words, when I send them to my publisher1.

I’m also trying to understand better the sequence2, the flow of images through the book – the different kinds3 of image, and the different moods they convey.

Some of the images are straightforwardly connected to the words beside them. Others are oblique. I like that mixture.

Filling In The Blanks

Some of the images I’ve created feel right for this book4, but I’m unsure at this point which words to put next to them.

I’m not rushing.

I just keep carrying the book around, and glimpsing at it as I wait for the kettle to boil, or whatever.

Sometimes an idea pops into my head5.

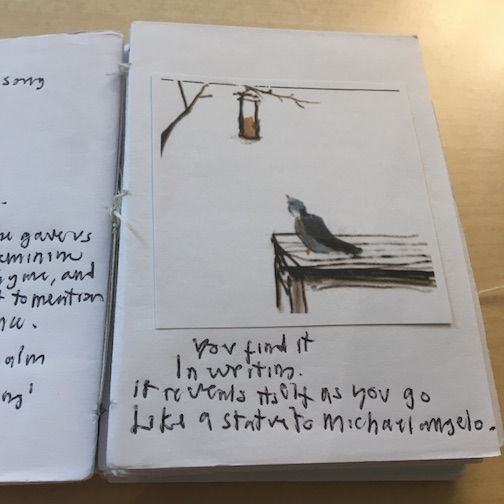

On other pages, I may have written the words already, and I’m waiting to think of a picture that might work.

When an idea comes to me, I make a sketch so I don’t forget what it is.

Later, I’ll print off a copy of the image and stick it on top.

How It Hangs Together

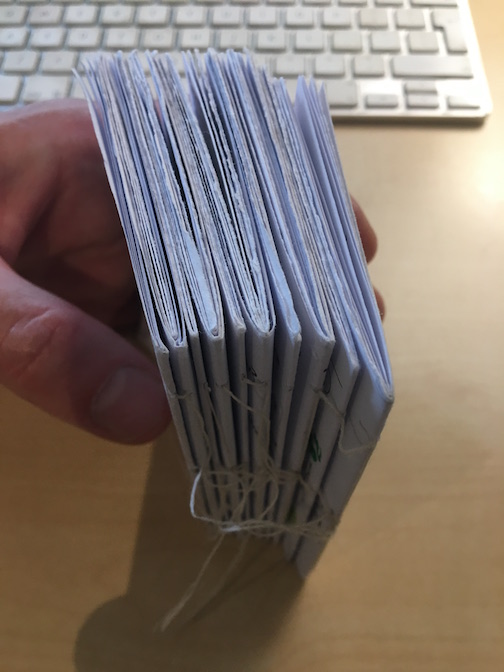

As you can see in the pictures above, the book is very loosely stitched together.

I positively resist making it “well”, because that might make it harder for me to tamper with it – add things, make a mess.

It’s made out of single sheets of ordinary A4 printer paper, folded into mini booklets of four pages (eight sides) each.

There’s room for roughly 50 images, and 50 poems.

It’s small enough to fit in the back pocket of my jeans.

Reputation

Yesterday I shared the opening paragraphs of a magazine story I wrote years ago, in which children robbed passengers on a London bus, and a link to the full story.

I wanted to let you read about the inspirational woman who turned those young people’s lives around – the inspirational woman I included in How To Change The World (part iii, chapter 4). I wanted you to get a sense of what she did, and why I was so moved and impressed by her when I wrote the book ten years ago.

I wanted you to get a sense of that before letting you know (if you didn’t know already) that the woman in question later experienced a serious reputational downturn.

The organisation she ran collapsed, and she herself became the target of much criticism in the newspapers and on the TV news. It was very public, precisely because she had become so high profile, with supporters including not only the editor of the Financial Times but also members of the royal family, celebrities (can’t think of a better word, sorry) and cabinet politicians.

Rightly or wrongly, many of these people dropped her.

It’s probably a deep-seated human instinct to pull away like that. I’m sure you could find many examples of it, throughout history. It’s certainly a feature of the times we live in. I’ve seen it happen to several people I interviewed as a journalist6.

I’ve always been impressed when they told me about the handful of individuals who stuck by them; even more so since I had a breakdown, in 2018, and – at rock bottom – felt sure that nobody want anything to do with me. So my instinct is to remain loyal to the woman I haven’t named yet.

But what does that mean, to remain loyal? On Amazon, somebody left a generally positive review of How To Change The World, but noted that this woman’s presence in the book was jarring7.

If that’s what he felt: fair enough. I’ve not been asked to re-write my book, so I don’t have to ask myself whether I should write her out of it. I hope I’d find a way to reframe what I wrote about her, acknowledging what happened afterwards but emphasizing what came before.

Perhaps I could weave her story into the afterword, in which (in 2011) I attempted to make clear that even the noblest work can have perverse outcomes, and with hindsight can seem discreditable. I gave a few examples of that, then wrote:

The point is not to be clever at the expense of people who almost certainly believed themselves to be doing something of real value (and not only for themselves). If we had been in their shoes and had their capabilities we would probably have done the same, and accepted the plaudits of people who told us that we were changing the world in a good way.

The fact is that anything we do might be characterised as unhelpful, if only by people far away from us, in time or space, who must deal with consequences that are hidden from us. Being aware of this, we are less likely to get carried away with messianic zeal, and that’s no bad thing. In changing the world, we can proceed with a degree of humility.

You don’t need to look in the footnotes for her name. It’s Camila Batmanghelidjh.

Word-Face

I can’t remember, right now, who came up with the metaphor of writers-as-miners, chipping away at the word-face. I’ve a hunch it was the poet laureate, Simon Armitage. But it could have been one of my other favourite poets, the late Adrian Mitchell. Or indeed somebody else. If I find out, I’ll come back to this page and update it.

Here’s why I mention it.

I promised yesterday that I’d write something about rhetoric, because I want to share something that’s often overlooked. Rhetoric isn’t only about finding a fancy way to express an idea you already have. At best, it can also be a way to find entirely new thoughts, by chipping away at one you aren’t quite happy with.

I wrote something about how I did that, taking one particular proposition and running it through a number of rhetorical figures. But I’ve written enough for now, so I’ll share that tomorrow instead.

Thanks for reading.

Thoughts? Send me an email

***

1 ↩︎ Just to be clear: I have a publisher already. I sent in some words and pictures in May, and my editor asked for some amends and additions. I find it very hard to do that if I rely exclusively on digital tools.

2 ↩︎ At risk of stating the bleeding obvious, the sequence has an effect on the overall experience. An obscure image at the start could put potential readers off going any further. Bright, colourful pics tend to be uplifting, black-and-white not so much. Too many pictures of people in succession, unless they’re starkly different, can make them blur together and stop the reader “seeing” them individually. Too few, and the reader may wonder where everybody has gone.

3 ↩︎ Portraits, landscapes, still lifes or whatever.

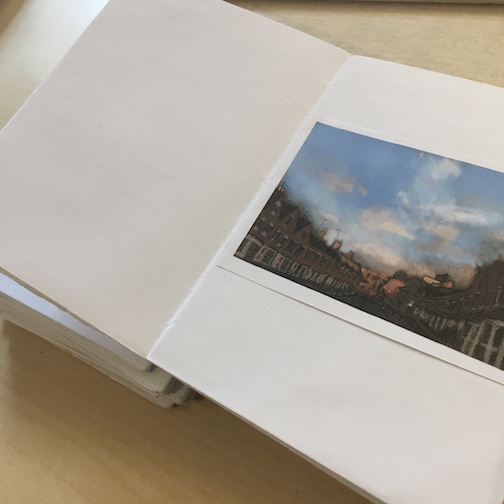

4 ↩︎ The book has a London theme, and I’ve made some pictures of places in London that mean a lot to me. I’d like to include them if I can.

5 ↩︎ Where do ideas come from? Honestly, I don’t know. My impro teacher, Keith Johnstone, taught me to think that God put them in my head. I don’t think he meant any particular god, though we never actually discussed theology. Some people call it “the universe”. People in 12-step fellowships use the term “higher power”. It doesn’t really matter (in this context, anyway) what you call it. The point is that ideas are gifts, and my job is to make myself open to receiving them, whether I’m waiting for the kettle to boil or doing something else. I recorded a short talk about this, entitled, Where Do Great Ideas Come From?

6 ↩︎ Others included the actor Chris Langham, whom I interviewed immediately after his release from prison, and the philanthropist Alberto Vilar, when his money ran out.

7 ↩︎ From that review on Amazon: “As a small footnote with perfect hindsight the inclusion of The Kids’ Trust [sic] strikes a slightly jarring note (I met the principal once at the height of her largely self-created fame and she struck me then as vain and vainglorious while being passionate and committed at the same time).”