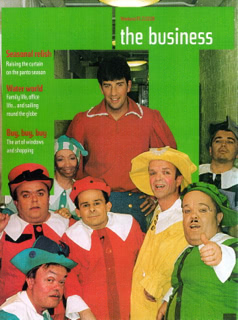

Snow White, seven dwarves

…and me

Originally published in The Financial Times

On stage, just yards from where I stand in the wings, Nurse Gertie adjusts her false bosom with a whack from each hand, then rushes into the stalls to cuddle a man in the second row. As she does that, some 1,500 people – mostly children – scream with laughter.

On stage, just yards from where I stand in the wings, Nurse Gertie adjusts her false bosom with a whack from each hand, then rushes into the stalls to cuddle a man in the second row. As she does that, some 1,500 people – mostly children – scream with laughter.

But from here, the stalls are out of sight, so I gaze towards the far side of the stage, where, standing between flat pieces of scenery, Linda Lusardi prepares to make her appearance as the Wicked Queen. Beside her, in the murk of dry ice, I pick out a Handsome Prince (the former Brookside actor, Sam Kane), and the Man in the queen’s Magic Mirror (played by Lionel Blair, who also directs).

When Gertie returns to the stage, she asks the boys and girls if they would like some early Christmas presents. As expected, they yell: “Yes!”, so Gertie turns to her left to request her cart full of goodies. And that’s my cue.

Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, welcome to pantoland. Specifically, welcome to Wimbledon Theatre, where pantomime has been a seasonal moneyspinner – and an opportunity for young children to sample live performance – ever since the theatre opened, on Boxing Day, 90 years ago.

Of course, panto has been going for longer than that. The seasonal performance of folk tales, with cross-dressing, topical jokes, and extravagant song-and-dance routines, is centuries old. Its roots lie in the commedia dell’arte , but its heyday was the 1800s, when shows such as Cinderella, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, featured Ali Baba and all 40 Thieves, as well as elephants, giraffes and a donkey. Pantos today are less lavish, but still fantastically successful, generating sufficient funds for theatres to stage more highbrow fare during the rest of the year.

To find out why panto is such a hit, I’ve come to Wimbledon to witness a production – Snow White and the Seven Dwarves – from the inside. Having joined the company at the start of rehearsals, I’m preparing to make my first appearance on the professional stage. For one night only.

The producer of this show is Qdos Entertainment plc, run by Nick Thomas and Jon Conway, former variety performers who moved into production in the early 80s. Their first panto, in Preston, was a disaster, because most families preferred, that year, to see Steven Spielberg’s ET at the cinema. But they overcame that feeble start, and gradually expanded until, in 1999, they bought out their biggest rival, E&B Productions. Today, operating under the E&B name – but sponsored by www.talentspot.com, a web site for performers – they produce pantos at 27 venues across the UK, with combined audiences of more than 2m.

If their success is not properly recognised, that’s because it is fashionable to look down on pantomime. As Thomas puts it, crossly: “A childrens’ TV producer once asked us, ‘Oh, do people still go to pantos?’”

Others in the business just don’t “get” panto. One actor, much loved for his part in a successful TV comedy, signed up for an E&B panto but couldn’t abide being booed, and had to be replaced at short notice. And an American, famous for playing Mr Sulu in the original Star Trek, could never be taught to say “Oh no there isn’t!” (He always inserted a pause: “Oh no. There isn’t.”) Still others shudder at the hefty workload: two performances a day, with just one day off each week. “But a lot of performers are tempted by the money,” Thomas affirms.

I can see why. “If you’ve heard of them,” Conway explains, “they get anything from £3,000 to £40,000 a week,” though only a few are paid at the top end of that spectrum. And if I haven’t heard of them? “They get £450.”

To maximise profits, Qdos puts on the same shows year after year, rotating them from one theatre to another. Props, costumes and entire casts are recycled, with scripts too remaining essentially the same. That way, the rehearsal period can be kept short.

WHICH BRINGS us to a converted church, in Waterloo, where the company first gathers just 11 days before the first night. The dancers, who need space, take the largest room; the principals take another; while Pops, Jolly, Blusher, Wheezy, Snoozy, Surly and Dozy crowd round a table in the hallway. (The more familiar dwarf names, copyrighted by Disney, are prohibitively expensive.)

For a day or so, it’s difficult to understand what’s going on. Typically, the rehearsal runs like this: in one corner, the musical director, David Roper, accompanies the Prince in a song. In the middle of the room, Lionel – everybody, in this context, uses first names, or “darling” – directs the Queen. On the far side, Nurse Gertie (Roger Kitter) and Muddles (Kev Orkian) practice slapstick. I can’t tell you what Mr Blobby does, because a fat legal agreement protects his identity, but I can reveal that Colin Oates charges onto the imaginary stage, bumping into people and knocking everything over.

As an outsider, I can’t help muddling the actors with their characters. I’m shocked to see Snow White (Emma Gannon) sit cross-legged in a corner and bite into… an apple! Equally jarring is the sight of the Prince, having finished a scene with Snow White, crossing the room to hug the Queen. (In real life, Linda and Sam are husband and wife.)

When I tell Lionel I’ve never been on stage before, he offers me the role of guard, responsible for pulling the queen’s chariot onstage. This is disappointing, but later, thankfully, he changes this to a small speaking part: the queen’s mincing hairdresser. Initially I feel awkward impersonating effeminacy, particularly since a significant portion of the company, offstage, manifests precisely that characteristic. But I do as I’m told: fiddle with Linda’s hair, wetly agree that she’s the most beautiful woman in the land, and bow so deeply I could wipe my nose on my shoes. (Possibly for this reason, Kev later tells me I’m the biggest bender in the show.)

Later still, Lionel grants me even more: a one-liner to deliver towards the beginning of the show; and the role of a courtier, with one additional word of dialogue – “whassup?” – which nudges my grand total into double figures.

The seven dwarves, meanwhile, spend much of the time flicking through tabloid newspapers, old copies of Hello!, and motoring brochures; breaking the routine every so often to run through their lines. Offering to help, I read the part of Snow White – promising to cook, sew, and keep the house tidy – and improvise sound effects: a loud snore and a thunder clap. That done, I tackle the Daily Mail crossword with Mr Blobby.

Meanwhile the dancers – four men, four women – work steadily through their routines, including one complicated number using broomsticks. Damian Jackson, the choreographer, leads them patiently through the movements three or four bars at a time. “One, two, three, four -and-uh…” he says, jabbing an imaginary staff, “five, six, seven, eight -and-uh…”

As director, Lionel chews gum and smokes simultaneously, rising from his chair every half minute to show how scenes can be played more effectively. Watching the amended performance, his face assumes an extraordinary expression: it’s like a grin, but with a wrinkled nose – suggesting all at once intense amusement and the detection of some foul odour.

And if he has enjoyed his revisions, he frequently rises again from his seat, shimmying over to ask: “Wasn’t that great!” To which the only polite response is a nod, or a gasp of “Amazing!” On the first day I find this coercive procedure amusing, but it soon begins to grate. Only after a week do I understand that Lionel’s unflagging enthusiasm is an invaluable tool, sustaining company morale through the endless repetition of jokes, songs and soppy love scenes.

Similarly, I learn to value the contribution of those actors who watch others’ reheasals attentively, laughing at jokes and supplying audience responses. (“Oh no you’re not!”, or “Behind you!”.) If it weren’t for Kev, endlessly willing to chuckle at my one-liner, I’d have crumpled long ago.

This mutual support becomes all the more important as difficulties arise. The first major problem concerns Kev. Although there will be a band playing at Wimbledon, the big musical numbers will use backing tracks supplied by head office. Kev, as Muddles, must sing Reach For The Stars, but the supplied track is in the wrong key: everybody agrees he can’t possibly reach the top notes, twice a day, without severe strain. Can the track be re-recorded?

Even more worrying is the health of Roger, who played Nurse Gertie last year in Nottingham when the production broke box-office records. Having recently undergone major surgery, he’s unable to attend the full schedule of rehearsals. Arriving late, he spends much of the time speaking on his mobile phone – to his doctor, presumably, or his agent. Will he make it?

To sort out these problems, Lionel spends hours negotiating by phone with head office. This is his 30th consecutive panto season: what can possibly motivate him to shoulder such troubles? “You’ll see,” he promises. “Just wait till the first night, when you hear the excitement of the children in the audience, on the tannoy in your dressing room. Then you’ll understand.”

On Friday, the full cast comes together for a run-through. Altogether, there are nearly 50 people in the hall: 16 “babes” – dancers aged between 8 and 13, trained by Bonnie Langford’s mother, Babette; their chaperones; lighting and sound technicians hoping to work out their cues; and a young American who’s come to watch Muddles. (Otter Ochampaugh is understudying seven different E&B pantos: yesterday he was in Woking, studying Keith Chegwin’s Buttons, as it were, in Cinderella.) That’s quite an audience, enough to put real vim into everybody’s performance, and Lionel, satisfied, dismisses us for the weekend.

But on Monday, when rehearsals recommence in a dingy working men’s club adjacent to Wimbledon Theatre – where technicians have started to install lighting and scenery – the energy level is low and the mood is glum. Performances, consequently, are flat. Even Linda, customarily cheerful and full of relish for her wicked role, falters: mangling one line, she cracks her whip and mutters “fuck!”, startling the assembled babes. (She immediately apologises.)

And so it continues until Wednesday, when we finally move onto the stage for the technical rehearsal, which proves to be interminable. The first two-and-a-half minutes of the show take 90 minutes. One problem involves Lionel’s mirror, which continually fails to light up on cue: fed up, Lionel eventually stomps offstage – in a tantrum rendered only slightly absurd by the fact that he’s wearing tap shoes. And four times, in the dwarves’ first scene, Wheezy (Kevin Hudson) builds up to a sneeze (“Aaah-aah-aah…”) only to be halted by a shout of “Stop!” as Tony Hudson, the company manager, walks on stage to announce some technical hitch.

Worse, Roger – having failed to appear on Monday or Tuesday – remains absent. Even Colin, his understudy, has no idea what is happening until the evening, when Jon Conway, flying in from head office, makes a decision. Shortly after he leaves, I overhear Colin phoning his daughter in the corridor. “Are you listening?” he asks. “Your daddy is now going to be Nurse Gertie.” He’s got less than two days to learn his lines, several changes of costume, and some complex slapstick. Meanwhile, somebody must be found to replace him as Mr Blobby (oops! the secret’s out).

That replacement arrives the next morning. Janchiudorj Sainbayar, a Mongolian circus performer, has never heard of Mr Blobby; nor is he familiar with Snow White. (In the stalls, while the “tech” drags slowly on, I tell him the story: at each twist, he raises an eyebrow and says “Aha!”) The general view, expressed backstage in whispers, holds that Sainaa (his nickname) is less than ideal as Blobby – but when he gets on stage, his physical comedy inside the unwieldy pink suit elicits voluble gasps of admiration.

That evening, at 6.00pm, we begin the dress rehearsal. Finishing shortly before 10.00pm, we go home; regrouping the next morning for Lionel to give his final “notes” (advice to performers). Several individuals are given useful pointers, but to me all Lionel says is that I must take care to push Gertie’s cart exactly to centre stage. Either I’m doing brilliantly, or else he’s willing to put up with anything for a bit of publicity in the Financial Times.

But after Lionel dismisses us, Sam wanders over to ask if anybody’s had time to help with my lines. At first, I assume this is a joke – I only have ten words – but no, he’s serious. “You’ve only got one gag, and you want it to go right. Take your time. Speak the words slowly: you’ll get a great laugh.”

WITH HALF an hour to go, the auditorium begins to fill, and loudspeakers in every dressing room transmit the hum of expectation. At last, I can feel the excitement that Lionel had prophesied. A surge of adrenaline reddens my cheeks, and my heart begins to race. Others too are visibly affected: withdrawing inside themselves to mutter lines in the shadows behind the scenery, or jerking through the movements of some complicated dance.

Then the curtain rises – to a huge cheer – and the dancers take their places in the dark. Then the lights come on, and suddenly Lionel has sprung from his mirror, Emma has joined him, and Colin has pedalled onstage on Gertie’s absurd tricycle.

In white tights that reach my armpits, lilac breeches and a scarlet blouse, I wait in the wings for my cue. Then I step forward, sobbing loudly till I reach centre-stage. Colin asks: “Who are you?” and that’s when, dropping my expression of unhappiness, I beam towards the bright lights: “I’m the town cry pish ! on snare-drum and choke-cymbal; and while the audience falls about – or so I hope – I saunter offstage towards Linda, Sam and Lionel.

But there’s no time to ask them how I’ve done. Offstage, I start running, pulling off the blouse and unbuttoning my breeches. Upstairs, in my shared dressing room, I step into a short dress, of the sort worn by men in the late Middle Ages, with fur-lined neck and cuffs. Sainaa zips me up, then I plonk a matching hat on my head and race downstairs. In the corridor, one of the dressers looks me up and down and says, “Don’t you look a right Mary?” and I catch a swagged sleeve on a door handle – but despite these delays I arrive precisely in time to take my place in the line of courtiers stepping onstage. And that’s when Linda makes her first appearance, to the concerted noise of 1,500 boos.

Soon after that comes my scene as her hairdresser – pout, bow, mince, skip – and when that’s finished, I hitch up my tights and find a perch in the wings to watch the rest of the show.

It doesn’t run entirely smoothly. The leading characters wear microphones, but these emit feedback, and sometimes fail to respond till after the first couple of lines have been uttered inaudibly. In the dwarves’ first scene, the backcloth snags on a row of lights: the stage remains dark until another cloth can be dropped instead. And three times a prop is accidentally left on stage at the end of a scene: one, Gertie’s red boot, is collected by the Prince in a brief moment of darkness following his proposal to Snow White.

But none of that matters. Our first audience is almost insanely happy, responding with astonishing force: hissing at the queen, squealing “Behind you!” at Gertie, and forcefully advising Snow White not to eat the apple. (Unaccountably, she ignores them.) That’s all to be expected, but more surprising is the volume, and duration, of cheers which greet Snow White’s revival by a kiss from the Prince: it doesn’t subside for practically a whole minute. Enjoy themselves? They love it.

At the end, I take my place between two of the dancers, and as the curtain rises we follow the babes to the front to take a bow, then step aside for the principals, one by one, to do the same. Then Lionel invites the audience to rise and join us in dancing to Robbie Williams’ “Let Me Entertain You”. Yikes: this is my longest continuous appearance on stage, and – standing beside the dancers – I’m acutely conscious of my limited wiggling skills. But eventually the curtain falls, rises, and falls for the last time.

“Thank you everybody,” says Lionel. “You were wonderful.”