Acting for all

It can make you appear supernatural

copyright www.stanislavskiexp.co.uk

Plato wanted the actors out of his Republic. But I'd call them back. And more than that, I'd have everyone be an actor – because performing teaches us to be more fully alive. It provides a lesson in existentialism that you couldn't match if Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus came back from the dead and recited their works to you in person. And it teaches you to be spontaneously creative – seemingly capable of dealing with anything life throws at you.

Over the last few decades, the general public's conception of acting has moved far away from what it once was: a resource that is readily accessible, to be witnessed in live performance at local venues. Partly, that's because of the increasing focus on award ceremonies, and celebrity, which enshrine the very small number of actors who get leading roles in large theatres. It's also because – though we use the services of actors more than we use, say, plumbers or opticians – the way we do that is all too often through some kind of screen, which can only add to the idea that these people are somehow unreal, and not like us.

But acting and performance lie within us all. Even in daily life we perform a role. The trouble is that this is often unconscious: to gain the greatest benefit, we need to perform consciously, deliberately – and with others.

But who am I to write this? By what authority do I make such claims?

Well, I'm English. I grew up in a country whose greatest cultural asset is drama, and the spoken word. The country of Shakespeare, whose works I studied for a masters degree. Additionally, I'm the son of an actor. My father, Ian Flintoff, has appeared in films, on TV, and in every kind of stage production: farce, thriller, revue and much else. He's appeared in tiny rooms at the Fringe, and on the mighty stages of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company. (That's him in the picture at the top, in a scene from Chekhov.) As I was growing up, he encouraged me to learn speeches by heart. (My brother specialised in Henry V.) Around the dinner table, I heard all about the plays he was in, and the ins and outs of rehearsals. When he appeared on TV, it would as likely as not be me who shoved a blank tape into the video and pressed record. It should probably go without saying that I thought this was the most extraordinarily glamorous work – and also important, though in a way that I couldn't quite have explained.

Aged about eight, I made my own first stage appearance as Moth, in my father's otherwise adult production of Love's Labours Lost. Dressed in a costume my mother had made, a black suit with lacy collar, I led four men across stage and delivered an impassioned address to the four women they loved. At first sight of me, the audience tittered, which I found distressing, but I was assured afterwards that they laughed only because I looked sweet. (This didn't entirely console me.)

But the ice had broken. I had appeared before others as someone else, and – like any other child, appearing in nativity plays at school or summoned up on stage at a panto by Widow Twanky – I'd been exposed to the reaction of an audience. Something expansive occurred, taking me out from myself into an awareness of otherness.

Was this acting? Not everybody would think so. The key thing, I believe, is that my appearance as Moth constituted a contribution, key to the effect of the scene – and I'll come back to that in a moment. I had not, it's true, prepared for the role with years at drama school and a deep understanding of acting theory, but you could say the same about the pre-pubescent boys in Shakespeare's own company, who first created the roles of Portia, Cordelia and Cleopatra.

If I had looked at the theory, what might I have learned? According to the great Russian acting teacher, Constantin Stanislavsky, everything in a play is done in order to achieve some kind of want. The formula can be summarised: what do I want (objective)? What do I do to get it (action)? What stands in my way (obstacle)?

This would have passed over my head at the time, but today I can see that precisely the same formula could be applied to our daily lives. When you act for performance, you come to understand something hidden in ordinary daily life, but which I've already hinted at: that you are acting all the time, playing a part – and you have the capacity at any moment to play a different part, and take your life in a new direction.

But putting the theory into practice is hard, as Simon Callow writes, in his classic book, Being An Actor. As a student at London's Drama Centre, “I submitted to the theory soon enough; but doing the really childishly simple exercises (I want the money. X has it. What do I do to get it?) proved impossible. We all had the most enormous difficulty thinking in terms of actions.”

So it needs to be taught.

Ivor Cutler

At my primary school we were blessed to have as a teacher, for one afternoon each week, the poet and eccentric performer Ivor Cutler. We had no idea that he was famous, and had appeared in films with the Beatles, but we couldn't miss the energy of his classes, in which he would ask us to perform scenarios both wildly entertaining (for us, anyway) and also (though we didn't know it) informed by the principles of drama-therapy.

(Therapists use dramatic techniques, like role-play, to help people overcome psychological conditions. A cynic might ask: if acting is therapeutic, why are some actors potty? As it happens, the actors I've met all seemed tremendously balanced and likeable. Actors themselves will testify to the loony quality of some among them. in his book Being An Actor, Simon Callow describes one old friend as, “the caricature of the self-destructive, demon-driven artist. He chewed whisky glasses, he picked fights…” But perhaps such individuals might have been even worse if they weren't actors.)

Sometimes, Mr Cutler would have us charging about as “Cowboys, Indians and Red Cross men”, variously firing pistols, discharging arrows, or dabbing medicine. Or he might put us in pairs, taking turns to spider and fly. Or we might walk in circles around the room as “American solders”, rolling a hip and twisting imaginary strands of chewing gum around our fingers, while Mr Cutler played boogie-woogie on the piano. These “performances” freshened our outlook on the violence of the Wild West, the savagery of nature, and the funny side of militarism.

At my comprehensive school, the drama teachers were idealists, fiercely motivated to open us up to the benefits and possibilities of performance. But they had their work cut out. I, for one, had become crushingly shy, and was reluctant to do anything the least bit remarkable on stage. The one time I did make an effect, it was only because I had inherited my role from another boy. I was obliged to laugh my head off at great volume, for some moments, until somebody silenced me by breaking an egg on my head. I remember with great satisfaction the expressions of my classmates, surprised that I was capable of pulling off this small instance of clowning.

Perhaps looking for a similar satisfaction, at around the same age I used to put on accents and stop strangers for directions in the streets near my home in West London. “D'ye ken the way tae Notting Hill Gate?” I might ask, on my way to a Scout meeting. (I did other accents too.) I haven't the faintest idea how I might have explained this to myself at the time, but looking back it seems clear that I just wanted to see what it felt like. Once, at a Chelsea v Newcastle match I dared to stand among the Geordies, and when one of them turned to me to ask a question, I consulted the programme and answered him in his own accent. He gave no sign of suspicion, and I turned back feeling gloriously successful. (Note: this time the satisfaction had nothing to do with impressing an audience. It was to do with pulling off a performance to my own satisfaction – and to the criteria I had set myself of being taken for the real thing.)

I was reminded of this, years later, when I watched the first episode of the TV documentary series Faking It, in which individuals were trained by experts and acting coaches to pass themselves off as something that they weren't – a DJ, a bouncer. After they had done this successfully – in the process discovering reserves of talent and sheer bravery that might otherwise never have been discovered – I was so moved by what I saw that I actually telephoned the channel's complaint line, to leave a message of heartfelt congratulations.

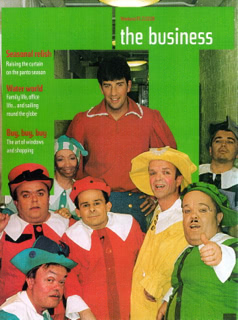

As I mentioned already, I didn't become an actor myself. Perhaps my father's achievements were intimidating. But I was always drawn to performance. Nearly a decade into my career as a journalist, I contrived to allow a magazine editor to send me to act in a professional pantomime. I started right at the beginning, submitting to a proper audition, and went through weeks of rehearsals, with Lionel Blair, Linda Lusardi, seven dwarves and Mr Blobby. I had four separate parts to play, with a grand total of ten words of dialogue, and like everybody else I had to dance at the finale, to Robbie Williams' Let Me Entertain You.

JP Flintoff and seven others in panto, FT Magazine

To mention these minor achievements feels ridiculous. But it would be shameful to argue that everybody is capable of certain experiences if I didn't mention some of my own. They are not intended to seem outstanding: they just happen to be mine. Feminists teach that “the personal is the political”, and if that's the case then the evidence to prove it will almost by definition appear rather ordinary.

But even small parts are important. Acting teaches us to recognise our effect on a given situation, no matter how small. And if we take that insight back into everyday life, we see that we can change the world.

I learned this in a conversation with Jonathan Pryce, whom I had been sent to interview by the Financial Times. He had been somewhat outspoken, some time previously, about having to work especially hard, in the National Theatre's production of My Fair Lady, because the person playing Eliza was not working hard enough.

I asked why this mattered to him. Why not leave her to be a useless Eliza, and get on with being a brilliant Professor Higgins? (I had no idea how much this question exposed my ignorance.)

Because on stage, he said, you are only as good as the people around you.

I asked him to elaborate. He drew a breath and said. “Imagine a powerful king on the stage. What does he look like?”

I shut my eyes and tried to picture it. “He has a huge crown,” I said. “And a huge throne. Covered in gold…?”

No, Pryce replied. “Those details only mean that he is king. What makes him powerful is the other people on stage, lying flat on their faces before him. If the same people got up and turned their backs to him, told jokes and smoked cigarettes, or had a snooze, the same king would no longer be powerful at all. In other words it's their behaviour that makes him powerful, not his.”

He was telling me that he could only be an imposing Professor Higgins if his co-star bowed down to him (as it were), demonstrating that she truly did believe, as Eliza, that he could change her life completely by his brilliance in teaching her to “speak proper”. But his insight had an explosive effect on me, because it seemed obvious that what he was saying must also apply to real life, off the stage.

Probably most people who read this will not actively be seeking to topple a powerful king, but when we grumble about “the system” or “the status quo”, we lose sight of our own complicity in the way things are. The status quo is like that powerful king Pryce described. If we don't like it, we must get up off our faces, turn our backs, and start to tell jokes. (Which is to say: Do Something.) Actors understand this: they know that they can bow down or get up, and produce entirely different effects. But if we are not actors, we may not understand that. In short, our own performances are what reinforce, define, and determine the performances that other “players” (in our daily, social, and political lives) can get away with. Existentially, one might say, that is the essence of politics – determining what actually takes place in the world.

So, in the Republic of Actors, we shall have statues of Pryce in every city. But if I have my way there will be even bigger statues of Keith Johnstone, whose work teaches how to move beyond the reticence of our “ordinary” everyday self, through improvisation, to a fuller mastery of “what’s going on”.

Today, Johnstone lives in Canada, but he grew up in London and worked as a teacher, amazing education authorities by getting the best out of the most unpromising school children, showing them to be talented and quick learners. His methods were unorthodox – he more or less allowed children to do what they liked – and the school wanted to throw him out, but a government inspector declared his results to be astonishing. In the last 1950s The Royal Court, then one of the leading theatres in Europe, came to hear about his extraordinary work and invited him to run workshops on improvisation for actors. The exercises he devised would become hugely influential. His book, Impro, published in the 1970s, remained a standard text at drama schools for decades.

Impro, by Keith Johnstone

Working with highly skilled actors, Johnstone was unable to understand initially why they seemed unable to improvise “ordinary” conversations. The scenes were always lifeless and unconvincing. An explanation dawned on him after he read about the research into animal behaviour, decades earlier, by the Austrian Nobel prize-winner Konrad Lorenz. Lorenz had concluded that animals are programmed to fight over resources as part of natural selection, and develop aggressive behaviours that, over time, cease to be obviously functional and become highly stylised. Johnstone wondered whether something like this might explain the particular quality of “ordinary” conversations that actors struggled to convey. Conversations are never motiveless, he concluded, but always freighted with dominance and submission.

Few of us recognise this sub-text, in ordinary life, but Johnstone found it everywhere. Inspired by his new insight, he asked actors to try again to make ordinary, “pointless” conversations. But he asked one to play “high status” and the other “low status”. (He used those terms because he feared that dominant and submissive might alarm them.) Their work was transformed. Scenes became compulsively watchable, even when Johnstone asked them to speak gibberish.

“Suddenly we understood that every inflection and movement implies a status, and that no action is due to chance, or really “motiveless”. It was hysterically funny, but at the same time very alarming. All our secret manoeuvrings were exposed. No one could make an “innocuous” remark without everyone instantly grasping what lay behind it.”

Over time, Johnstone made many startling discoveries about everyday dominance and submission. He found, for instance, that it's impossible to be neutral. A greeting of “Good morning” might be experienced as lowering by a manager but as elevating by a clerk. No action, sound, or movement is innocent of purpose.

Johnstone discovered for himself what the anthropologist Desmond Morris was to spell out slightly later in the 1960s, in The Naked Ape: that posture gives away status. A still head, for instance, conveys dominance, while constantly touching the face is submissive. He noted that if you ignore somebody, your status rises and theirs falls. Conversational tics give the game away too: a short “er” at the start of a sentence functions as a submissive invitation to be interrupted, while a longer “errr…” means “don't interrupt me, even though I haven't thought what to say yet”. Interestingly, actors didn't need to learn every little signal to benefit from Johnstone's insight: knowing only to keep their heads still, for instance, to show dominance, they tended instinctively to adopt the other tell-tale signals.

It's easy to see how useful this kind of insight might be in daily life – which is why highly paid executives and public figures take coaching from actors.

Interestingly, Johnstone found that dominance is neither better nor worse than submission. Both have their uses, as everyone will come to understand, in the Republic of Actors. Johnstone enjoyed playing low status himself, to remove students' fear of failure. On first meeting a new group he would sit on the floor and say that if the classes proved a failure the students should blame him. Though he was playing submissive, his status was rising fast, because only a very confident and experienced person would put the blame for failure on himself. Almost without exception, students would start sliding off their chairs to the floor, uncomfortable to be higher than him.

The important point is that status (as Johnstone uses the word) has nothing to do with social class. As Sartre and Camus might have said it's not what you are, but what you do. You can be low in status, but play high, and vice versa. For example:

TRAMP: ‘Ere! Where are you going?

DUCHESS: I'm sorry, I didn't quite catch…

TRAMP: Are you deaf, as well as blind?

But to read this is not enough. To really understand it, you need to do it. You have to act.

Students who worked with Johnstone learned to become more spontaneous, and creative. People who habitually said no became people who said yes, and embraced whatever opportunities they were given.

Keith Johnstone workshop, London 2012. (JP Flintoff second left)

The means by which they were transformed were acting exercises. On stage, Johnstone explained, anything the other actors do can be called an “offer”. If actor A holds something out to Actor B, Actor B could accept the offer by saying, “You remembered my birthday!” The opposite of accepting an offer is blocking. Thus, Actor A might reply: “It's not my birthday.” (We should not confuse this “blocking” with the term professional actors use for plotting moves and actions on stage.) When one actor blocks the other, it's deeply frustrating and causes everything to stall. But we block, on stage and in life, because we tend to be scared of whatever we don't control. Johnstone taught actors to stop blocking, and accept anything – with sensational effect.

“Good improvisers seem telepathic,” he writes. “Everything looks pre-arranged because they accept all offers made. The actor who will accept anything that happens seems supernatural… unbounded.” He's absolutely clear that this awareness of blocking could help in real life too. “People with dull lives think their lives are dull by chance. In reality, everyone chooses what kind of events will happen to them by their conscious patterns of blocking and yielding.”

Learning to accept, or yield, drives home the lesson that, far from being individuals, alone in the world, we are always and utterly locked into relationships with the people around us. It does not mean always submitting to them, or dominating, but allows a third possibility: fruitful collaboration. To see what this might be like, try playing the Sentences Game with friends. Each person contributes just one word at a time to a sentence: everybody shares some responsibility for the (usually) bizarre sentence that develops, but no one individual has more responsibility than any other. It's genuinely collaborative and can yield a great deal of laughter.

I hope by now that I've given a reasonable idea how much we might all benefit from a world in which everybody acts. But how to bring it about? I quite like the idea of a national service – calling up young people to put in a year of training, and regular top-ups throughout later life, like the Swiss army. Might this produce a certain amount of resistance? Possibly, but even professional actors who yearn for work are reluctant to get stuck in at times. As Simon Callow puts it in Being An Actor, “the atmosphere at a first read-through suggests a group of people who have been called up, or press-ganged”. They soon get over it.

To some extent, it might help to recognise how much we all perform already (and not only in the sense, already noted, of “playing a part” in everyday life). Right now, as I type, I can hear my wife, who has never shown interest in being an actor herself, read a story to our daughter. I can't hear very clearly, but can tell that she is reading Roald Dahl, because every so often she adopts a grating German accent – to convey that author's Grand High Witch. It's a very funny performance, albeit for a tiny audience.

The German playwright Bertolt Brecht had great respect for the capacity of ordinary people – that is, non-actors – to perform. In perhaps his most celebrated essay, The Street Scene, Brecht asked what an actor might learn from the way in which an eyewitness describes a street-accident. This eyewitness often turns out to be an exemplary actor, even adopting different voices to play the parts of the people involved in the accident. But the eyewitness doesn't attempt to pass himself off as embodying the things he describes. If a bystander asks him to clarify, he does so.

How to take things further? There are no funds to build more theatres. But that's not the only way. The late Ken Campbell used to take touring groups of actors into unconventional venues, including pubs. He once advocated closing down the Arts Council for five years. Theatres would close, he conceded, but that was no loss because they were mere museums. “Actors who really wanted to act would act. In streets, pubs, fish-and-chip shops, canteens, transport cafes. And I guess that their standard of acting would improve. They would earn their bread only if they took those people there, at that time, on a real journey. They would become masters of the fading arts of contact with an audience… instead of being the safe, subsidised, castrated toys of the middle class and the bourgeoisie.”

We could all learn from Campbell (who clearly also deserves a statue). We don't need new buildings, we just need a new spirit. It was something like this idea that motivated my father, several years ago, to set up a nationwide festival of Shakespeare to coincide with the Olympics. Sport is for everybody, the authorities proclaim: school children must learn to run, and hop, and jump. Why not acting for all, too? Children watch plays, films and programmes – should they not, as with sport, also take part in the action themselves? Run – and act. Swim – and sing. High jump – and dance. The actor's union, Equity, got behind the idea, as did the RSC, but more exciting is the fact that grassroots groups from John O'Groats to Lands End have signed up to do some kind of Shakespeare performance in 2012.

I, for one, will certainly do my bit to join in – a spot of Hamlet, perhaps, or Julius Caesar. Perhaps I shall get my brother involved, and we can do Henry V. I don't know yet whether we'll do it at home, standing on kitchen chairs, or in a pub, or on a bus – but we shall certainly do something. But what about you? What will you do?

This story first appeared in the 2012 edition of The Idler, on the theme of “Utopia”. In the event, hearing nothing from my brother for a few days, I did some Henry V myself